Cinelandia is an imaginary city in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by deserts and built in disparate styles: “it has a certain touch of Constantinople, with a mixture of Tokyo, a certain touch of Florence and much of New York”. Governed dictatorially by Emerson, the boss of the movie industry, all kinds of adventurers come to live there, hoping to build a career and become rich. This story belongs to a novel written by Ramon Gómez de la Serna (1888-1963). A prolific author, inventor of a special kind of surrealistic aphorisms called Greguerías, he produced a great number of novels, most of them comic. He wrote the script for Los Caprichos, an early film by Luis Buñuel, and came into contact with Picasso and the Dadaist movement. But he was unique, “a unipersonal generation” as someone called him, fully immersed in surrealism, the de-humanized art of the time. Cinelandia is, of course, a parody of Hollywood, and the novel was published in 1923.

It was the era of silent films, which had created a huge industry everywhere; it was no different in Spain, where the people were, and still are, extremely fond of this kind of entertainment. The advent of sound films around 1930 caused the collapse of the cinema studios, mainly in Barcelona. A difficult new start was attempted at a time of economic crisis. It was also a time of enjoyment, when the II Republic, turbulent as it was in politics, gave the Spanish people a new sense of freedom and joie-de-vivre. The first talking picture produced in Spain was titled I want to be taken to Hollywood (Edgar Neville, 1931) and shows the fascination the American movies had for the masses. American competition made it difficult for the Spanish producers to make much progress, but in 1935 a total of 24 films were on the screens, some of them with great popular success. The civil war of 1936-1939 caused a new collapse and made the new start difficult. Due to the imposition of a clerical culture by Franco’s regime, the forties and the fifties were, as theatre critic José Monleón called them, “an endless Holy Week”. The incipient industry produced mostly films adapted to the ruling ideology: plenty of religious films, lives of saints and miracles in convents, also patriotic and historic stories. General Franco was himself a film lover and had written the script for one of them: Raza (race). For lighter entertainment the public was given numerous love stories featuring the pop singers known as folklóricas, Lola Flores, Carmen Sevilla, Antonio Molina, and many others.

Sara Montiel, for a time an exotic Hollywood star (“Vera Cruz” in 1954, “Run of the Arrow”, etc.), was a folklórica of a new kind. Frivolous and sensual, she specialized in a more cosmopolitan vaudeville reminiscent of the “roaring twenties”. Her time represented a new opening. As of 1962, the government started to subsidize the film industry to compensate for the overwhelming competition from the United States and also from the movies coming from France and Italy. Of course, censorship acted decisively to protect the morals of the Spaniards. Many good foreign films were simply banned, obliging film-lovers to travel to nearby France to watch them (Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris caused a massive exodus to Perpignan, which was very embarrassing for the Spanish authorities). Others were shown in Spain after being severely mutilated. Politics and progressive ideas were mostly suppressed, erotic scenes cut to a minimum. I remember seeing some of my Spanish friends reading film criticism in foreign magazines to learn what the movies were really about. Spanish filmmakers, in this atmosphere, had a hard time, but made very remarkable films. Of course they could not create in the modish French style of the “Nouvelle Vague”, but some neo-realistic films had quality and were very successful. They were really “virtuoso” in the art of circumventing censorship. Luis García Berlanga, to mention just one, developed a great skill in this kind of simulation. His films are a very faithful reproduction of the poor and repressed society he lived in, and their humor was lethal for the established prudery and the official optimism. But they contain many metaphors and hints which were difficult to denounce as political criticism, and are full of tender humor. Reality itself was the most effective parody of the social mores.

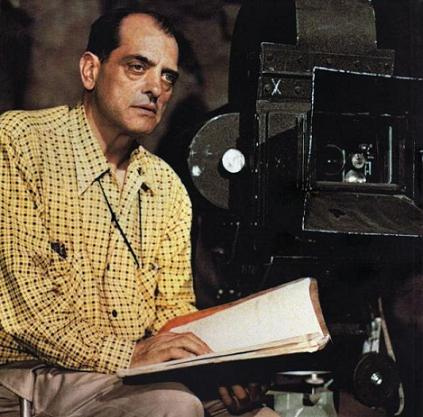

Of course, the great personality of Spanish cinema was Luis Buñuel, a true genius and an important figure in universal culture. From 1939 until the end of his life in 1983 he lived outside of Spain, in the U.S. and in Mexico, so that he did not have to suffer the limitations of censorship. He was free and thoroughly used his freedom. Born in 1900 in a small village in Aragón, poor and surrounded by dry fields, he was the son of a rich businessman, a returning emigrant from the Americas (indiano), where he had made his fortune. He soon revealed himself as a natural leader and a person of powerful imagination. Intelligent and strong in mind and body, amateur boxer, violinist and hypnotist, he could not stand the repressive education of the Jesuits of Saragossa and went to Madrid to continue his studies. He was lucky. His parents found lodgings for him in the prestigious Residencia de Estudiantes, the meeting point of the liberal, educated bourgeoisie of the capital. His friends there were no less than the poet Federico García- Lorca and the painter (and writer) Salvador Dalí. He met Ramón Gómez de la Serna and other writers and embarked upon the provocation and challenge of surrealism.

He went, like so many Spanish artists, to Paris, where he learnt how to make films. He was determined to shock and insult the bourgeoisie and he started with a film he made together with Dalí: Le Chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog), an improvised mixture of dreams and sado-masochistic images. In 1931 he went back to Spain and became involved in the politics of the II Republic. He enrolled in the Communist Party and did his best to free himself of the reputation of petitbourgeois that was normally attached to surrealism. To this end, he made the impressive documentary Tierra sin Pan (Land without Bread), which crudely depicted the extremely poor region of Las Hurdes, in the North of the region of Extremadura. He served the propaganda of the Republican cause through cinema. In 1939 he was in the U.S. working in Hollywood and New York and could neither go back to Spain nor adapt to the American way of life. He then went to live in Mexico, where he spent the rest of his life. His best films were made in France and Spain in the sixties: Tristana, Viridiana, The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie. These and many others come to mind, together with their main characteristics: they use images taken from dreams and the subconscious mind, they give voice to the rebellion against religious taboos and sexual repression, they defend human liberty and compassion for the poor and the oppressed. Buñuel´s style is very personal and unmistakable. Ingmar Bergmann once said: “Buñuel almost always made Buñuel films”.